Copyright © 2022 Foshan MBRT Nanofiberlabs Technology Co., Ltd All rights reserved.Site Map

In nature, many organisms achieve unidirectional water transport through their unique multi-scale surface structures and asymmetric wettability, such as desert beetles, cacti, and spider silk. The surface structures of these organisms have inspired humans to design efficient water management materials. In recent years, unidirectional water transport materials have received extensive attention due to their unique microstructures and spontaneous liquid transport properties. Electrospinning technology, which is enabled by electrospinning machines, has been widely used in the preparation of unidirectional water transport materials because of its advantages such as simple process, easy adjustment, high porosity, and controllable pore size. These materials show broad application prospects in fields such as fog-water collection, oil-water separation, wound dressing, air filtration, and intelligent clothing.

This paper systematically analyzes the mechanisms, structures, and applications of electrospun unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes. The research focuses on three different structural types of unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes (Janus structure, sandwich structure, and biomimetic structure), and comprehensively reviews their applications in fields such as fog-water collection, oil-water separation, wound dressing, air filtration, and intelligent clothing. Finally, the challenges and future development directions of electrospun unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes are summarized.

(1) Mechanisms of Unidirectional Water Transport

The research first analyzes three main mechanisms of unidirectional water transport: the wettability gradient effect, the differential capillary effect, and the biomimetic transpiration effect. The wettability gradient effect refers to the difference in wettability of different regions on the material surface, which enables the liquid to transfer from the hydrophobic side to the hydrophilic side. The differential capillary effect is based on the rise or fall of liquid in capillaries with different pore sizes or properties. The biomimetic transpiration effect mimics the water transport and evaporation process of plants and achieves anti-gravity unidirectional water transport through a multi-level branching network structure. These mechanisms provide a theoretical basis for the design of unidirectional water transport materials.

(2) Three Structural Designs of Unidirectional Water Transport Nanofiber Membranes

Janus Structure: It consists of two fiber membranes with different wettabilities. By adjusting the fiber diameter and membrane pore structure using an electrospinning device, unidirectional water transport can be achieved. For example, Qin et al. prepared a PU/(PAN/PVP) bilayer nanofiber membrane by electrospinning technology. Through surface modification, unidirectional water transport from the PU layer to the PAN/PVP layer was realized (Rd = 967%).

Sandwich Structure: Composed of two outer materials and one inner material, it has higher mechanical strength and multifunctionality. For example, Zhang et al. prepared a PAN/PVA - TPU sandwich-structured nanofiber membrane. By adjusting the surface energy gradient and pore structure with an electrospinning device, unidirectional water transport from the hydrophobic side to the hydrophilic side was achieved, with a water vapor transmission rate as high as 9760 g/m²·d.

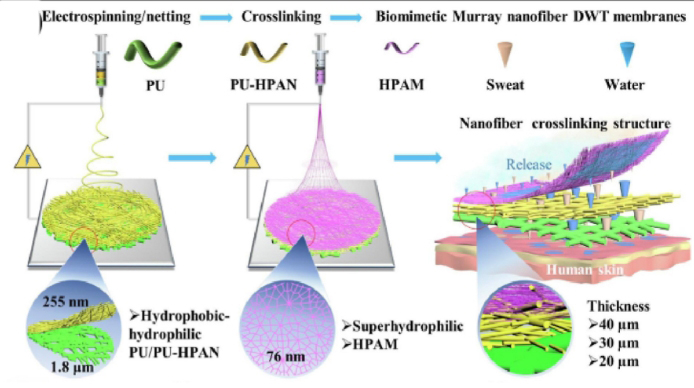

Biomimetic Structure: It mimics the water transport mechanism of plants and realizes efficient unidirectional water transport through a multi-level branching network structure. For example, Wang et al. designed a biomimetic Murray nanofiber membrane. Through the leaf vein-like surface structure, rapid water transport and evaporation were achieved (Rd = 1245%).

(3) Application Fields of Unidirectional Water Transport Nanofiber Membranes

Fog-Water Collection: Unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes can efficiently collect fog water from the air through their unique structural design. For example, Wu et al. prepared a PAN/superhydrophilic PAN nanofiber membrane. When fog droplets contact the hydrophobic layer, small droplets gradually coalesce and move to the superhydrophilic layer under the action of capillary pressure differences. The water collection rate of this structure is as high as 6.76±0.75 g/cm²/h, which is more than 6 times that of a single-layer hydrophilic membrane.

Schematic illustration of water harvesting for directional wicking membranes.

Oil-Water Separation: Janus-structured nanofiber membranes exhibit excellent selective permeation performance in oil-water separation. For example, the PLA-CNTs/PLA-SiO₂ Janus membrane prepared by Qin et al. has a contact angle difference of 140° on both sides, a separation efficiency of >99% for oil-in-water emulsions, and a flux as high as 1485 L/m²/h. When an oil-water mixture is dropped on the hydrophobic side, water quickly permeates through the membrane while oil is intercepted.

Preparation route and oil-water separation process of Janus PLA hybrid fiber membrane.

Wound Dressing: Unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes can quickly drain wound exudate, keep the wound dry, and promote healing. For example, Shi et al. spun hydrophobic PU nanofiber arrays onto hydrophilic microfiber networks. By using the wettability gradient, the wound exudate was pumped from the hydrophobic side to the hydrophilic side, avoiding wetting around the wound. Animal experiments showed that this dressing increased the wound healing speed by 30%.

Schematic design of a self-pumping dressing: the self-pumping dressing pumped the simulated biofluid and left little simulated biofluid around the wound bed. Reproduced with permission.

Air Filtration: Unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes show high-efficiency particulate matter interception and antibacterial properties in air filtration. For example, the PAN-β-CD/PCL-ZnO membrane prepared by Xu et al. has a hydrophilic layer that adsorbs PM2.5 and VOCs with a filtration efficiency of 99.99%, and a hydrophobic layer that keeps dry through unidirectional drainage to prevent bacterial growth. In a hazy environment, this membrane can be used continuously for 72 hours while maintaining stable performance.

Schematic diagram of PAN/β-CD/PCL/ZnO Janus nanofiber membrane prepared by electrospinning technology and its application in PM, VOC filtration and directional water delivery.

Intelligent Clothing: Unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes can quickly transport sweat on the skin surface to the outer layer for evaporation, keeping the body dry. For example, the biomimetic Murray three-layer nanofiber membrane prepared by Chen et al. has a water transport index of 1270% and an evaporation rate of 0.86 g/h. Volunteer tests showed that wearing clothing made of this material can reduce the body surface temperature by 3 - 5°C.

Schematic of preparation of biomimetic Murray nanofiber DWT membranes. Reproduced with permission.

The innovation of this paper lies in systematically summarizing the mechanisms, structures, and applications of unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes and proposing future development directions. The research has achieved various structural types of unidirectional water transport nanofiber membranes through electrospinning technology and demonstrated their excellent performance in multiple fields. However, there are still many challenges for its large-scale industrial application. Future research should focus on developing multi-functional composite materials with low cost, environmental friendliness, and excellent performance to promote the development and application of related technologies.

Electrospinning Nanofibers Article Source:

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymer.2025.128221